Fire, Paint, Pastels | Stones, Fans, Gum

on writing with nontraditional media and supports

Sometime in 2016, a box of gas station Super Bubble chewing gum caught my eye. I had recently published Azure, my cotranslation of Stéphane Mallarmé with Blake Bronson-Bartlett, and while working on that project I learned that Mallarmé wrote poems on nontraditional supports like stones and fans; when I saw the gum, I thought, Why not? and bought the entire box.

I landed on a formal constraint of four words per piece of gum, two with the same color ink and two with different colors than the first two and each other (altogether red, brown, and black). I streaked the backs of each with a black Posca marker to ensure the viewer could easily differentiate between the written-on and blank sides, arranged them in various configurations on a white sheet of paper, and photographed the variations.

Several reading possibilities emerged. For example, one could read the pieces of gum as they appear in the image itself, allowing the image to be the poem (or poems), like in the image facing this page. Or one could transcribe each piece of gum as its own poem: “worm takes pink drink”; “woofers smiling crowding sun”; “tiger gums toughen up.” Or transcribe a specific ink or combinations of inks in individual images or across the entire series (“worm takes crowding tiger gums”). And so on.

After working with the gum, I kept at this mode of writing, moving on to artist notebooks and pastels, which defamiliarized my writing hand because they were often thicker, stubbier, more uncomfortable, and dirtier than a pencil. I became more attuned to the idiosyncrasies of my handwriting and the densities and acoustics of different pastels, and to their textures, colors, potentials for smudges, dust effects, and so forth. I could only write out characters comfortably and legibly at a larger size, which shortened my line lengths and made it so that I sometimes had to break words apart, opening possibilities for foregrounding embedded words and effects like the spininess of hyphens at the ends of lines. I largely composed on the spot. Not having endless sheets of paper or an open document to work with necessitated developing new techniques—among them rhyme, homophones, repetition, transitions, images, references, and tonal variations like humor—for maneuvering through finite spaces. The logic of these new approaches eventually took root in my nonvisual poetic compositions. It changed my language—or helped me access a new language.

I had been writing poems with a pencil, pen, and word processor since I was a kid but began to use different media and supports to see what was possible in line with an intrepid forebearer, Mallarmé, and in the spirit of poets like William Blake, Louis Zukofsky, Josely Vianna Baptista, and Jean-Michel Basquiat—poets who in their respective ways interrogate the glyphic, spatial, transtemporal, aerated, juicy, object- and image-based potentials of the poem. In addition to a new language, I acquired a new practice: visual art.

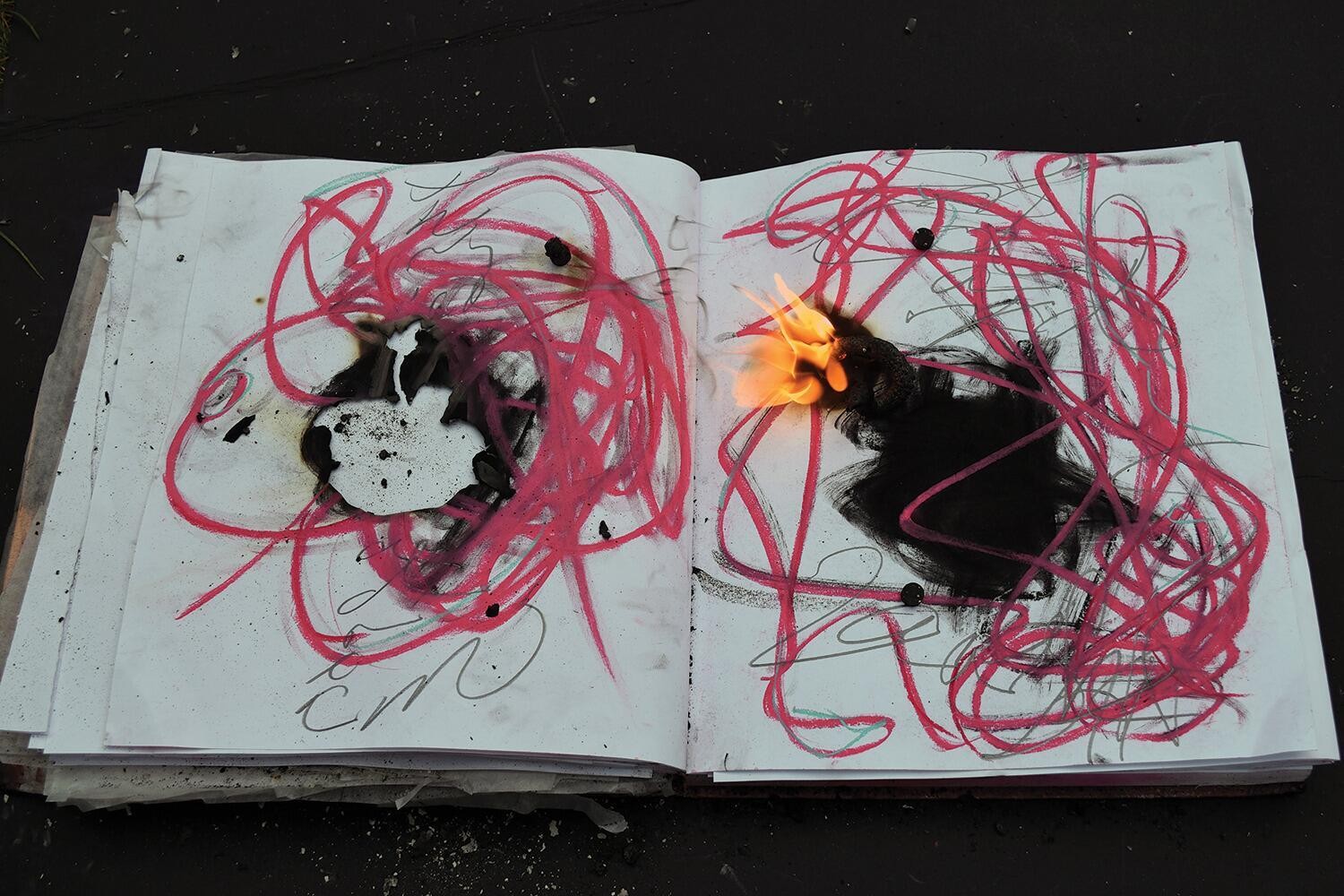

My work with nontraditional media and supports culminated in an art book, Grand Grimoire, completed in 2016. culebras [snakes] is a series in Grand Grimoire that was made using pastels, pencil, spray paint, and fireworks on paper in a 12.5-by-10.75-inch sketchbook. The poem’s text, which is written throughout culebras, includes words from Emily Dickinson’s “A narrow Fellow in the Grass (1096),” D.H. Lawrence’s “Snake,” and Theodore Roethke’s “Snake.” I have chosen to normalize the poem’s layout and not incorporate the post-fireworks changes (e.g., lacunae); elsewhere in Grand Grimoire and other work, I transcribe the poem’s distinct layout and physical changes. The first image is a title page—the word culebras in pastels with some smiling cobra eyes drawn through the hood-like loops of my handwriting/drawing. I photographed the fireworks’ aftermath in every image but the last, culebras 6 (thrice adream | smeared laughter), which captures them igniting and where you can see some of the Pharaoh’s serpent, aka Black Snake firework pellets, scattered across the page.

What helped me persist through early doubts was the sheer pleasure of engaging with the materials—an embodied, erotic response, to use Audre Lorde’s word, to the cool, flat sides of the pastels, the thickness of the paper, the sound and smell of drips of paint. I had no clue where it was going, but it was fun.

culebras

landowner | priest

little fellow | garden mop

gardenia sheets | folded in pasta

mottled shade | splashing in water

thrice adream | smeared laughter

Poet and editor Robert Fernandez was born in Hartford, Connecticut, and grew up in Miami. He earned an MFA at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and is the author of the collections We Are Pharaoh (2011), Pink Reef (2013), and Scarecrow (Wesleyan University Press, 2016). He is also the co-translator, with Blake Bronson-Bartlett,...

-

Related Articles

- See All Related Content